CAN I LEARN TO RESIST THE REWARDS OF PARTICIPATION?

on michaela coel, neolithic trading + las vegas

I should love Las Vegas less. I know I should. I know that excess is fragile and empty and that it disappears faster than liquid smoke from a bell jar-encased cocktail, the kind on every bar menu in this city. But fragile and empty excess is the most authentic thing in America. How could I resist its mecca?

I’m here for work, which is the truth but it feels like a lie. Travel journalism is a strange line of business and one that I thought I had left for good. I began the job about seven years ago, with the great delusion that eventually I would discover some essential insight into human nature, buried in some culture halfway around the globe. But the only thing I discovered was that most travel journalism today is rebranded marketing. PR companies give writers drinks and comp’ed dinners with the intention that they’ll write about them. And it sounds like a dream, but the whole thing feels performative and transactional if you care (even slightly) about pesky things like ethics.

In the months before the pandemic, I traveled to Scotland and Dubai and Lake Tahoe. I flew until the cities blurred and I became so jaded that if there was any essential insight into human nature, it seemed to be: don’t bother. It’s all just money. The only time I felt anything real was when I fell snowboarding and literally broke my ass. Then I couldn’t leave the hotel and while all the other journalists were on the mountain, I was hobbling around a Reno casino with an ice pack shoved down the back of my jeans. And on that trip, I decided that I wasn’t going to write about travel anymore. I decided that I was going to stand up for my ethics and that I wouldn’t take any more free trips in exchange for free advertising. Yet almost exactly three years to the date of that proclamation, I’m back on a press trip, writing about spas and restaurants and other places where people can spend money.

Walking the Las Vegas Strip yesterday, I passed a man drumming on an upside-down paint bucket. As a very tanned man with a very large gut and a cut-off t-shirt approached, the drummer started chanting, “LET’S GO BRANDON!” The man laughed, fished his wallet from his pocket, and threw the drummer a few bucks. When he walked away, the drummer moved eye contact to the next group and started chanting, “LET’S GO BIDEN!” The man in the cut-off looked back in shock.

Las Vegas doesn’t owe anybody anything except the illusion of a meaningful experience. It’s no coincidence there are so many magic acts in town. It’s a trick of a city. More of an idea than a real place.

Each time I go down to the casino floor, I pretend that I’m playing slots but really I’m watching middle-aged men wander the neon circus. They walk slow, eyes panning the place with expectation. They’ve been told that fantastic things — unmentionable things — happen here. They come in packs, on pilgrimages, hungry for a weekend they’ll only talk about in close company. But none of these men seems to achieve it. The closest they come to transcendence is a blackout.

***

Just a few days before my flight to Vegas, I was scrolling Instagram in bed when I saw that Michaela Coel had filmed a BMW commercial. Sure, it was under the guise of a statement about filmmaking, but it was still definitely a commercial and I was like cnbtebkktuiw5yiwbrwhebryq35g noooooooooooooo.

When “I May Destroy You” premiered, I watched it over and over again. I loved the show’s ethical ambiguity, a reckoning with morality seen too little in pop culture, and began looking to Coel for career direction. In her acceptance speech at the Emmys for “Best Writing,” she delivered:

“Visibility these days seems to somehow equate to success. Do not be afraid to disappear.”

When I packed up my things and moved out of New York City a few months ago, it was with six words ringing in my mind: “Do not be afraid to disappear.” I was going to start taking my writing seriously. I was going to make something of myself, stop binge drinking until the bars closed, stop accepting every single invitation, stop spending so much time on the carousel of nightlife. And that meant that I had to disappear.

Almost instantly, I felt better. My mind cleared up. So did my skin. I stopped drinking. I started writing more and started writing better. The things that happened every time I left the city happened again — but this time, I started to hold onto them. I wanted them to be my personality instead of my vacation.

So I settled into a slower life in the suburbs. I started thinking about what it would be like to stay there, get a job at one of the local colleges, teach writing and tell stories about the person I used to be. I settled into peace with the idea of disappearance. I knew that I liked myself more when I disappeared. I didn’t think about what this meant — or that the message implicit in Coel’s speech was that disappearance was only okay if you eventually reappeared with a product.

***

In my reappearance into the travel world after years away, the only thing I feel is slight detachment. Vegas doesn’t seem like a hotbed of sin to me. It doesn’t seem like much of anything at all, to be honest. It’s a hollow city for hollow experiences. The closest I can get to any emotion is, “Of course it is.”

You know, I haven’t even gambled here. Not once. There was one evening when all I did was lie in bed, eating leftover smoked salmon from the Giada restaurant and watching “The Banshees of Inisherin.” (Mumbling “that’s what you get for waking up in Vegas” to myself.) Every 15 minutes or so, I’d hear thunder from the streets.

It was the fountains at the Bellagio. I had seen them in action, of course, in all the movies and promotional materials. But I hadn’t realized that the fountains loudly rumble when the weight of the water smacks back down into the pool. Each wet fight against gravity is timed to music and so the crashes echo like thunder does in the summer.

Earlier that day, I was walking by the fountains when the whole scene came alive to the tune of “Viva Las Vegas.” I stood next to a man who positioned his cell phone against the concrete barrier and started filming. When the song ended and the fountains disappeared back into the Bellagio pool, the man straightened up and looked around, phone still filming. “Was that it?” he asked. “One song?”

The show is always shorter than we imagined it would be, the Mona Lisa is always smaller. Tourism is never the adventure we tell ourselves it will be.

Yet, despite this knowledge, despite knowing that the $9 black coffee on the casino floor is nothing short of a rip-off…it feels like we should travel? Or perhaps like it’s our right?

Particularly when our daily lives are at the service of somebody else’s profit — when our time is not our own to manage — travel becomes the one place we can imagine freedom. We wander different cities and fantasize about how different we would be if we lived there. Our priorities would finally be set right. We’d find the group of people with whom we belong. We would take siestas! Travel is intoxicating because it’s the closest we can get to our imagination in real life.

***

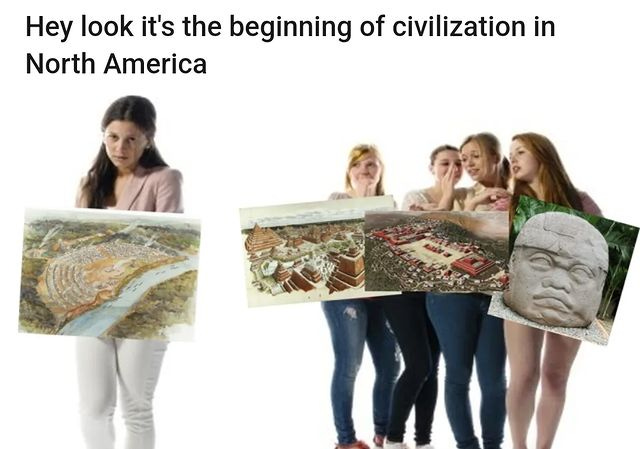

On a tangent that isn’t quite a tangent…I’ve recently become obsessed with Poverty Point (thanks to its appearance in “The Dawn of Everything” by David Graeber and David Wengrow). The World Heritage Site in Louisiana dates back around 3,400 years and is home to the largest earthworks in the Western Hemisphere. What’s surprising isn’t just that this place is incredibly archaeologically significant yet most of us have never heard of it. What’s surprising is that although people traded goods at Poverty Point, it wasn’t necessarily a marketplace. It was a place where people traded ideas.

The site is considered particularly rare because it was built by people who were hunter-gatherers. Most archaeologists considered it possible only for agrarian (farming) societies to build a metropolis of that size. In “The Dawn of Everything,” Graeber and Wengrow assert that this archaeological site is proof that movement, building, and trade are not reliant upon economic systems and that, in fact, we can divorce our understanding of what is possible to build from what is possible to fund.

This aspect of Poverty Point haunts me: it didn’t grow from a surplus of crops but rather some mysterious urge to connect and exchange the intangible. It is proof that a city can rise without any business to sustain it. Or, at the very least, that at one point in human history, this was possible.

According to Graeber and Wengrow, in many pre-colonized Indigenous communities, travel was seen as a form of mutual aid. You were obligated to welcome nomads into your home with the knowledge that if you set off on the road one day, you too would be welcomed anywhere. I keep thinking about this. What would travel look like if it wasn’t linked to capital?

Today, our adventures are hemmed in by what we can afford. Travel is a commodity, one measured and policed by wealth. This morning, I paid $30 for a medium black coffee and a breakfast sandwich made with what I can only describe as Velveeta cheese. Do we know how to travel without tourism? Will there ever be another Poverty Point?

***

Upon further reflection, it’s not disappearance that makes me afraid. I didn’t need Michaela Coel’s reassurance when I left New York. In fact, I think I relish each opportunity to drop off the grid. It’s reappearance that scares me. I don’t know how to move in the world with integrity. I can’t hold onto my values (shaky as they may be) when I want to make money, when I want to eat at the Giada restaurant, when I want to see the world and try to understand it. In the name of economic survival, do we all find ourselves doing things we thought we’d never do? I’m writing generic copy about spas along the Las Vegas strip. Michaela Coel is doing a BMW commercial.

I watched the commercial again, just to see if I had any right to be offended.

Coel, in a pastel blue leather trench coat, walks by a BMW. And she’s almost saying something profound. She’s almost delivering some wisdom about the craft of storytelling.

“That’s the beautiful thing about perspective, there’s always more than one,” she says. And she repeats it. And if you follow the prompted link, you find that BMW is giving away a few filmmaking grants.

It’s almost noble. It’s almost a good cause. Coel’s words are almost insightful and the program is almost generous. But if there’s one thing I’ve learned in Vegas — between the free cocktails and the comped dinners — it’s that nothing is truly generous if it makes sure you know its name.

HI! THANKS FOR MAKING IT TO THE END. HOPE U ENJOYED UR READING EXPERIENCE! NOW IT’S TIME TO REMIND U THAT PHILOSOPHY FOR PARTY GIRLS IS A READER-SUPPORTED PUBLICATION.

CONSIDER BECOMING A PAID MEMBER FOR ACCESS TO BONUSES LIKE:

VIP POSTS

MEMBER-ONLY CHATS

MONTHLY PLAYLISTS

READING RECOMMENDATIONS

UNFILTERED ACCESS TO MY BRAIN